About the study

This project, conducted between January and July 2022, is funded by the Transformation Fund, and developed by the Global Diversities and Inequalities (GDI) Research Centre in partnership with local authorities Islington Council, Lambeth Council, Haringey Council, and local charities, including Afghan Association Paiwand, Afghan Association of London, Migrants’ Rights Network and Living Under One Sun.

The humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan has forced thousands to flee their homes. Images of Afghans clinging to planes at Kabul airport, shone a spotlight on the desperation of those trying to flee the new Taliban regime. The British government evacuated approximately 17,000 people from Afghanistan between April and September 2021[1].

Afghan organisations in the UK quickly mobilised to provide services and resources to support the new arrivals[2]. Despite the UK government’s claims to support those seeking to leave Afghanistan, the ‘hostile environment’ and the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 continue to curtail the rights of those seeking asylum in the UK.

Drawing on the experiences of diverse Afghans in London, this project provides valuable data on these important issues and makes recommendations for how services and support could be improved.

Aims and objectives of the study

Working with Afghan organisations and peer researchers, this study aimed to:

- Understand the needs of diverse Afghan communities in London.

- Explore the particular experiences of recently arrived Afghans, especially evacuees.

- Assess how different agencies and associations are responding to the needs of Afghans and what more needs to be done.

Project overview

Multi-method study:

Interviews, focus groups and walking interviews.

- Ethical approval from London Metropolitan University research ethics committee.

- Participants have been pseudonymised to protect their identity.

Afghan participants: sample description

- 30 Afghan people took part in the study.

- 20 interviews and 4 walking interviews, 2 focus groups.

- Recruited through the peer researchers.

- 7% (17) identified as female, and 43.3% (13) identified as male.

- 5 stakeholder interviews.

- 2 directors of migrant organisations and 3 employees of local authorities.

Focus groups: sample description

Conducted face to face at two community organisations, one in South London and one in North London.

Focus group 1:

Involved only female participants (8) including a peer researcher who provided support with translation when needed.

Focus group 2:

Involved 7 participants (3 men and 4 women) including 2 peer researchers who supported the setting up of the focus group; no translation was required.

On the 15th August I was in Afghanistan, when the Taliban took over the control of Kabul, I was in the city… I tried too many times to go inside the airport, unfortunately the Taliban were firing at the people… So I decided to escape from Kabul, and I was crying when I left my country.

(Mirwais)

- Professor Louise Ryan

- Dr María López

- Alessia Dalceggio

- Najiba Askari

- Khandan Danish

- Farid Fazli

- Samiullah Khaillyzada

Evacuation from Kabul airport (Aug 2021)

- Chaotic situation at airport “worse than it was seen on TVs” (Liqman).

- Those staying for 2 days outside the Baron Hotel, processing centre, mentioned the lack of any facilities including toilets.

- People waded through a canal of filthy water in search of British soldiers.

- Desperate efforts were made to get through the crowds and be processed, despite having the correct documents.

- British authorities were suspicious of fake emails and reluctant to accept documents at face value.

- All expressed their gratitude to the British authorities for being evacuated.

- However, many vulnerable people were not evacuated.

Safety and Security

- Participants raised concerns about close family, including wives, children, siblings, aged parents, and friends still in Afghanistan.

- There was particular worry about the safety for those from ethnic minorities (for example, those of Hazara background), human right activists or whose families had been connected to the previous political regime or the military.

UK Hotels

- ‘Bridging hotels’: mostly central London high end hotels for evacuees.

- ‘Contingency hotels’: for those who arrived via other routes (including irregular routes) often offer far less support, cheaper and lower quality accommodation than bridging hotels.

- Participants praised the role of NGOs.

Housing

- Rehousing: big concern for people in hotels.

- Lack of transparency and information from Home Office (HO).

- Several key informants from local authorities said that they had identified properties in their boroughs but the HO had not found families to take up these properties.

- Several of our participants have now been relocated by the HO from central London hotels to cheaper hotels across the country.

- By summer 2022, almost 10,000 Afghans were still in hotels. In August, the HO started to advise people to find their own rented accommodation[3].

Employment

- Long term residents in London: had rebuilt successful careers.

- Many had established successful businesses in London.

- Many of the second generation had graduated from university and obtained professional jobs in areas like accountancy and law.

- Among the recent arrivals, especially those who were still in hotels: general sense of frustration about the slow process in securing the right to work.

Education and de-skilling

- More than half of our 30 participants were highly educated.

- Education was seen as a route towards social mobility and economic stability.

- Educational achievement was perceived as a marker of success in their own migration experience and for their children.

- Participants were keen to reactivate their careers in Britain but worried about de-skilling.

- This was particularly the case for recently arrived refugees but also women from the established community in London.

- Language barriers were identified as a cause in participants’ experience of de-skilling.

- Childcare was often a factor in women’s access to English language courses.

Professional Networks

- Lack of professional networks.

- Several Afghan students, who had come to the UK on scholarships, expressed concerns about their employment prospects despite gaining qualifications from British institutions.

Discrimination and Racism in London

- Most participants reported not having experienced overt racism in Britain.

- Several praised the multiculturalism in London.

- However, some did experience racial comments, microaggressions and what they understood as structural racism in the UK.

Dilaram mentioned stereotyping of Afghan women:

When I was saying I am from Afghanistan they were shocked, ‘Oh how did you come as an Afghan woman, how did you manage to come to the UK, because I know Afghan women cannot go outside, I know Afghan women cannot go freely everywhere?’ […] whenever people outside the country see you as an Afghan woman they automatically stereotype you.

(Dilaram)

Gender

Many participants mentioned:

- restrictions and violence against women because of so-called ‘traditional’ values in Afghanistan.

- However, some participants praised men’s efforts to adapt to the new situation in the UK.

- Several people highlighted pockets of resistance among some more traditional Afghan men in the UK.

Generational differences

Spokespersons from Afghan community organisations summarised the range of services provided across the generational spectrum:

- Saturday schools for young children.

- Youth clubs and sports activities for teenagers.

- Women’s clubs.

- Support for those Afghans entering older age.

The established Afghan community in London has started to do well. However, the community is diverse. There are specific concerns about Afghans living here without official documents, working cash in hand and living with friends. As a key informant who had worked at the Afghan embassy in London explained:

“We don’t know exactly but these are likely to be mostly young, male and single”

As the community grows and enters the second-generation other challenges emerge such as family issues and inter-generational communication.

There are some cultural issues… a sort of clash between the families sometimes because the children have grown up here but the parents are the first generation of refugees here so they give a hard time and don’t understand each other

(A key informant from an Afghan organisation)

Recommendations

Based on our findings and in conversations with our advisory group and with our Afghan participants at dissemination events, we have developed the following recommendations:

Government and Security Forces – need to learn lessons so that mistakes are not repeated in any future evacuations.

Home Office – need to increase staffing and reduce bureaucracy to ensure a speedier and more efficient processing of asylum applications.

Foreign Office and Home Office – should work quickly with international partner organisations to facilitate safe relocation of those at risk, still inside Afghanistan, including the vulnerable relatives of evacuees.

Home Office and Local Authorities – faster and more effective communication and cooperation is needed to ensure the rehousing of thousands still in temporary hotel accommodation.

Home Office and Job Centres – should cooperate to deliver better communication regarding Afghans’ right to work.

Statutory Bodies – should provide appropriate and long-term funding to services for Afghan migrants beyond emergency response.

Funders – enable NGOs to provide specialist counselling for victims of trauma including culturally sensitive and appropriate forms of support.

NGOs and statutory services – coordinate efforts to assist new waves of arrivals, including undocumented and recent refugees, to access accurate and appropriate information.

Statutory bodies, local authorities and NGOs – ensure accurate information to new arrivals regarding the costs of living in and outside London especially in the context of spiralling energy costs.

Job Centres, Professional organisations, educational institutions and employment agencies – to coordinate to provide fast reaccreditation of qualifications and support reemployment of refugees.

Employers, including Afghan businesses – provide internships and work experience opportunities for new arrivals.

Local Authorities and Education Providers – coordinate school provision for Afghan school children after relocation from bridging hotels.

Local Authorities working with NGOs – ensure adequate provision of supplementary support and education to children especially those hit hardest by the disruption of the pandemic and evacuation.

Local Authorities working with NGOs and specialist services – provide information about hate crimes/incidents, discrimination, and routes of reporting.

NGOs and specialist charities – enhance awareness and address gender-based violence and encourage women to engage in activities outside the home environment.

Local Authorities, NGOs and statutory services – work together to address the care and needs of the emerging elderly Afghan population.

Content

We would like to express our gratitude to our two Afghan community partners, Afghan Association of London and Paiwand Afghan Association. We also wish to thank the members of our project advisory board who provided such helpful advice throughout the project: Fizza Qureshi (Migrants’ Rights Network), Helena McGinty (Lambeth Council), Karim Shirin (Afghan Association of London), Seana Graham (Haringey Council), Tianna Smith (Haringey Council), Aleena Majeed (Paiwand), Fahima Zaheen (Paiwand), Deenaa Ram (Paiwand), Leyla Laksari (Living Under One Sun), and Sue Lukes (Islington Council).

We wish to express a special thank you to our four wonderful peer researchers without whom this project would not have been possible: Najiba Askari, Khandan Danish, Farid Fazli and Samiullah Khaillyzada.

We are grateful to London Metropolitan University for funding this project through the Transformation Fund. We also wish to thank our colleague Maeva Khachfe for all her work supporting this project.

Finally, we want to thank all the participants who gave so generously of their time and who shared their powerful and very moving stories with us. This report is dedicated to them.

The study was conducted by a research team from the Global Diversities and Inequalities (GDI) Research Centre, based at the London Metropolitan University, and four peer researchers from two specialist Afghan organisations, the Afghan Association of London and Paiwand. The research team was led by Professor Louise Ryan, Director of the GDI Research Centre, and Dr María López, Deputy Director of the GDI Research Centre. The peer researchers were Najiba Askari, Khandan Danish, Samiullah Khaillyzada and Farid Fazli. The research assistant was Alessia Dalceggio.

The research was designed in partnership with an advisory board which included members of London’s local authorities Islington Council, Lambeth Council and Haringey Council, and four local charities, the Afghan Association of London, Paiwand, Migrants’ Rights Network and Living Under One Sun. The research was reviewed and approved by the London Metropolitan University’s Research Ethics Committee and was conducted between January 2022 and July 2022. The study was funded by the University’s Transformation Fund.

The humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan has forced thousands to flee their homes. In preparation for the drawdown of the UK armed forced from the country, around 15,000 Afghan and British people were evacuated in what was called Operation Pitting. Although the British Government did not publish a breakdown of the figures, it was reported[4] that approximately 5,000 people of those evacuated during the operation were eligible for the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP), a scheme aimed at providing relocation and assistance to people who worked with or for the UK government and/or UK Armed Forces in Afghanistan and to vulnerable Afghan nationals. Female politicians, members of the LGBTQ+ community, women’s rights activists, and judges[5] were among those who were called forward.

A further separate scheme, the Afghan Citizens’ Resettlement Scheme (ACRS), was established to resettle Afghan people most at risk of human rights abuse, such as women and girls, members of ethnic and religious minority groups as well as LGBTQ+ individuals. This scheme is being kept under review and aims to resettle up to 20,000 individuals in total.

The Afghan Citizens’ Resettlement Scheme has come under criticism for its prioritisation of people already in the UK. The Refugee Council already reported an increase of asylum applications from Afghan people since summer 2021[6], and multiple stakeholders were concerned that this delay in opening the scheme to people in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries, coupled with the absence of other safe/accessible routes, would likely result in people resorting to make unsafe journeys to the UK[7].

The Home Office provided Afghan people resettled in the UK with emergency ‘bridging accommodation’. This type of accommodation was set up mostly in hotels and was meant to be a temporary measure until individuals’ needs were assessed and more permanent solutions were organised[8]. However, over one year after the initial cohort of people arrived in the UK, very few people have been provided with permanent accommodation and indeed it is particularly difficult to find accurate figures as to how many people have been rehoused and how many still remain in hotels. During a parliamentary debate on the 6th of January 2022, the then Minister for Afghan Resettlement, Victoria Atkins, reported that approximately 4,000 individuals had been or were in the process of being moved out of temporary accommodation[9], leaving approximately 12,000 people still in bridging hotels. Indeed, in August 2022, the Guardian newspaper reported that 9,500 Afghans were still in temporary hotel accommodation[10].

Meanwhile, Afghan organisations in the UK struggled to cope with the demand for their services and the scarcity of volunteers as well as resources to support new arrivals[11]. Yet, under the UK government’s ‘hostile environment’ policy, the rights of asylum seekers have been severely curtailed. The Nationality and Borders Act 2022 further reduces these rights. Moreover, the Government policy of ‘off-shoring’ people seeking asylum to Rwanda indicates the hardening of immigration policies.

This project aimed at providing valuable data on these issues, drawing on the rich narratives of Afghan people, both recently arrived and more established migrants, as well as the views of key stakeholders. We hope this research will help to inform the strategic planning of migrant organisations, local authorities, and other key stakeholders and service providers.

Working with Afghan organisations and peer researchers, this study aimed to:

- Understand the needs of diverse Afghan communities in London.

- Explore the experiences of recently arrived Afghans, especially evacuees.

Assess how different agencies and associations are responding to the needs of Afghans and what more needs to be done.

The research is a multi-method study which included interviews, focus groups and walking interviews.

This project received ethical approval from London Metropolitan University’s Research Ethics Committee. All participants were given a sheet providing information about the study, the way in which their data were going to be treated and instructions on how to withdraw from the study, should they wish to do so. Translation was provided where required. All interviews, focus groups and walking interviews were subject to informed consent. All participants have been pseudonymised to protect their identity.

Afghan participants sample description

Overall, thirty Afghan people took part in the study. Most participants were recruited through the peer researchers, and consideration was given to the diversity of the sample in terms of gender, age, family situation and time of arrival.

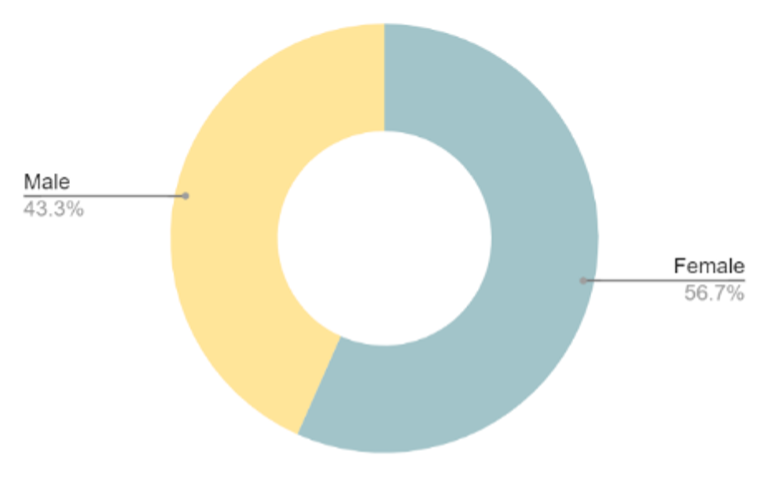

Just over half (56.7%; N 17) of our participants identified as female, and 43.3% (N 13) identified as male.

Image 1. Participants’ gender

Route and year of arrival in the UK varied greatly among participants, with just over half (53%; N 16) of our participants having arrived between the years 2020-2021 (i.e., student cohort and recent arrivals). For a detailed discussion on route of arrival please see Key Findings, Section 1. Diverse routes of arrival and immigration barriers.

|

Route |

Student |

Recent arrival |

Previous wave |

Marriage |

Other |

|

No of participants |

4 |

12 |

8 |

5 |

1 |

Table 1. Participants’ route of arrival

Interviews

We conducted twenty interviews with newly arrived and long-established Afghan migrants in London to identify their perceptions and needs. Most interviews were conducted face to face, while eight were conducted online using MS Teams. Some participants who were interviewed individually also took part in focus groups. Furthermore, we conducted four follow-up walking interviews with participants who had all been included in the previous round of interviews. All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded, fully transcribed, and anonymised to protect confidentiality.

Focus groups

To further understand and capture the diversity and richness of participants’ everyday experiences, we carried out two focus groups,. The focus groups were conducted face to face at two community organisations, one in South London and one in North London. The first focus group involved only female participants (N 8), including a peer researcher who provided support with translation as needed. The second focus group involved seven participants (three men and four women) including two peer researchers who supported setting up the focus group. In this focus group no translation was required.

Walking interviews

We conducted four walking interviews with participants who had already taken part in individual interviews. Using a location of their choice as a starting point, these walking interviews were conducted around the area to understand how participants navigate their local environment, the extent to which they feel a sense of familiarity and belonging in specific places in London and any obstacles they encounter in building local attachments.

Follow up emails

To track any changes in circumstances, over time, we established email contact with all the newly arrived participants within our sample. We are keeping in touch electronically with them, specifically to understand whether they have been or are going to be rehoused. Nearly a year after they first arrived, very few have been rehoused in permanent accommodation and several have been moved to hotels outside London.

Stakeholder interviews

We also conducted five interviews with key stakeholders, including two directors of migrant organisations and three people from different London local authorities. These interviews were all conducted online using MS Teams. The interviews with these key informants were crucial in helping us gain relevant background information and to inform our understanding of the current context, especially the challenges facing recently arrived refugees and the services engaging with them.

Working with peer researchers is a key aspect of participatory research and ethical good practice[12]. That is not to suggest that peer researchers are simply used as cheap labour for data collection purposes. In our project, although we had a tight time frame and limited budget, we sought to work closely with the peer researchers to shape and inform the study. Our four peer researchers were identified and recruited via our two Afghan partner organisations. The peer researchers were provided with online training, and we had regular communication via WhatsApp and email. Moreover, except for one peer researcher who moved outside London, we met with the peer researchers in person on several occasions, including at the focus groups and some individual interviews, where they provided assistance with translation, as well as during visits to the community organisations and for dissemination events. The peer researchers played a key role in the recruitment of participants. Because two of the peer researchers were recent arrivals, they were well placed to connect us to people in the same cohort, including several who were hotel residents. It is largely due to the endeavours of the four peer researchers that we were able to access such a wide variety of participants, especially those still located in the hotels. In this way, the peer researchers were instrumental in shifting the key focus of the project to include more recently arrived evacuees. We invited the peer researchers to share their reflections with us in this report and two have provided the following as brief summaries of their experiences.

Najiba Askari

I am writing about my experience of doing research with Afghans in London. It was an interesting job because I met more people and heard their different life experiences in London. Some people experienced a challenging life and some of them were similar to my own life in London.

Actually, after the crisis in Afghanistan, I was looking for a volunteering job in order to take a small part, along with others, to help Afghan refugees. When I heard about this project I sent my CV and after the interview I was very excited for this opportunity to be involved in the research project run by the team from London Metropolitan University.

Therefore, I learned from this project effective communication and management skills. I also had a chance to work and meet experienced researchers and learned how to have good collaboration with colleagues.

Although I did have professional work experience in Afghanistan, since I came to the UK, 5 years ago, I did not do office work or anything similar to this project because of my lack of confidence.

Working as a peer researcher makes me more confident and gives me motivation for other work. It was like a key for a better start. Now, I am more confident about other jobs and familiar with confidentiality, patience and priorities during work. I am also able to manage meetings or other programs on time.

Khandan Danish

As an Afghan woman who left everything behind and experienced emigration in exile, I knew what it meant to be a refugee. Therefore, I got interested in getting involved in this research with Afghan refugees in London in order to give back my time and expertise to my own community.

I believe my previous experience working with the Afghan community, helped to reach out to relevant Afghan refugees and therefore helped this research project to be more insightful.

In the meantime, being involved in this project, working with a professional research team from London Metropolitan University, has enabled me to transfer my knowledge in a new setting and to develop new skills and knowledge.

1. Diverse routes of arrival and immigration barriers

Among our thirty participants there were many varied routes and periods of arrival. Some of our older interviewees had left Afghanistan in the 1990s when the Taliban first came to power. For example, Ahmad Shah had visited Europe on many occasions for business reasons and after the Taliban came to power, he claimed asylum in the UK in 1998. Since then, he completed a PhD and built up a successful career working with NGOs and with various local authorities in London, specialising in the area of equality and diversity.

We also interviewed participants who arrived via unofficial routes, including both recent and some more long-established residents. Rabiya, her husband, and small son fled Afghanistan in 1997, over land via Tashkent in Uzbekistan, on to Russia and then across Europe via Poland in a journey that took almost one year and relied upon a succession of traffickers. Her story resembles that of one of our most recent arrivals, Sher Shah, a young man who travelled via Iran, Turkey, Greece and then on to France before finally arriving in the UK in the autumn of 2021 when he claimed asylum. In both cases, although separated by over two decades, the participants relied on very expensive people smugglers and took huge risks to seek sanctuary. These accounts indicate the enormous lengths that people are prepared to undertake when fleeing danger[13].

Four of our participants had arrived in 2020 on prestigious scholarships to study at British universities. These participants had all competed at the highest level of academic achievement to attain these highly coveted opportunities. In all cases, their plan was to complete their Master’s degrees and return to their jobs in Afghanistan. Of course, these plans were turned upside down when the government collapsed in 2021. Unable to return home, these four had to apply to change their status from student visas to asylum seekers. This process proved slow and complicated. Indeed in at least one case, the student ended up becoming status-less as his student visa expired before his asylum claim was processed. This had serious implications for that man’s access to resources including support for his disabled child.

Among our participants, there were also ‘marriage migrants’. These five women had entered the UK to marry Afghan men already resident in the country. Begum for example, arrived in 2018 to marry her husband who had already lived in London for over 10 years and was a British citizen. The couple had one son aged two years. Begum, a university graduate, had worked for a large international NGO in Kabul before her marriage. She is now attending English classes and hopes to return to work once her son starts school.

Ten of our participants were recent evacuees who had left Kabul airport in August 2021. Their narratives recounted very similar experiences of the appalling conditions at the airport and around the processing centre at Baron Hotel. These experiences will be discussed in more detail later in this report (see section 2. Evacuation from Kabul August 2021). While the evacuation process was terrifying and chaotic, a notable feature of their accounts is the suddenness of their relocation. The disruption of their lives occurred quickly and unexpectedly as the government collapsed and they were forced to flee at very short notice; within days they found themselves in London. As Nasreen, a young woman, explained: ‘suddenly the situation changed, and we just come here and now we are here.’ A sign of her unanticipated relocation was the fact that she only brought one bag: ‘I just had one bag that was my laptop and that’s all, I didn’t bring anything with me…My laptop and my phone… I didn’t bring my charger!’. The suddenness of their arrival contrasted markedly with the long, slow, protracted journey over land and sea undertaken by those who came via different routes such as Rabiya and Sher Shah, mentioned earlier.

Of course, it would be simplistic to assume that all our participants neatly fitted into specific migration routes and categories. As the experiences of the students mentioned above illustrates, immigration status can change over time in unexpected ways. Some of our participants had travelled back and forth to the UK on numerous occasions and via different immigration routes. For example, Gulkan originally arrived in London in 2011 for work-related reasons. He later returned to Afghanistan and was again posted back to London with his job in 2017. Gulkan expected to return home, but these plans were suddenly disrupted in 2021 with the rapidly changing political events in Afghanistan. Thus, like the students mentioned earlier, Gulkan had to apply to change his status and suddenly found himself claiming asylum in the UK. Having occupied a high level and respected position in Britain, Gulkan now finds himself immersed in the slow and highly bureaucratic Home Office procedures without any power to expedite the process. Having had his initial Home Office interview in November 2021, he explained: ‘I’m telephoning the Home Office every month, up until now [March 2022] … they say, ‘Wait, you have to wait’.

Mirwais had also spent time in the UK in the past. Mirwais and his family had visited Europe regularly for business reasons and had travelled to the UK for holiday on tourist visas. ‘I used to come to the United Kingdom several times when I was [working] in Paris. My wife and my kids, they came several times here for a visit, families or holiday.’ But now, like many others, Mirwais finds himself in very different circumstances and caught up in the uncertainty of the Home Office system:

my expectation was that I have visa when I arrive to the UK, I can apply for family reunion to bring my kids, they are depending to me. So since six months I’m here, I stop in a hotel in South London, honestly speaking, I am an asylum-seeker now.

Because of their concerns about the safety of their families in Afghanistan, many of our participants were desperately pursuing ways to bring relatives to the UK. Nasreen was especially concerned about the security of her sister, who had been a sportswoman in Afghanistan: ‘my family are also worried about her because it’s hard for a girl if the Taliban know her that she was a sports woman… the news said that Taliban are kidnapped many women. The last week 29 women just gone.’

Our data show the diversity of routes that Afghan people have taken to come to the UK over more than 20 years. Our findings illustrate how people’s experiences and opportunities are shaped by the wider political context and events that operate beyond their control. These findings also show how circumstances can change suddenly, in unexpected ways, with consequences for immigration routes. Even those who had previously held secure roles and immigration status can find themselves plunged into new and unfamiliar situations as they navigate complex, slow, bureaucratic processes. Beyond the participants themselves, it is also apparent that immigration barriers are having serious implications on family reunion and causing untold stress and anxiety. Despite their deep concerns about the safety of close relatives, including wives, siblings and parents, participants are struggling to navigate the immigration regulations to achieve family reunion in the UK. Hence, there is urgent need to ensure that proper legal advice is available to help support people through the complex maze of immigration regulations.

2. Evacuation from Kabul August 2021

We interviewed a significant number of people who had been part of the recent evacuation from Kabul Airport in August 2021. A common theme among our participants was the speed with which their ‘normal lives’ in Afghanistan had suddenly fallen apart when the Taliban seized power in the summer of 2021. As Liqman, a male evacuee, stated:

I myself didn’t expect that this thing, this kind of situation … we didn’t think that after 20 years everything would be collapsed, organisations, governments, everything would collapse and we would be forced to leave Afghanistan.

All the evacuees described the chaotic situation at Kabul airport. As Liqman emphasised: ‘It was I think many, many times worse than it was seen on TVs’.

Nasreen, who was accompanying her elderly grandmother, described ‘there was a lot of people, and everyone was pushing each other’. Ebraheem, who went to the airport with his wife and young children, including a baby, became so fearful for their safety in the crowds that he advised his wife to return home:

Look at this crowd, if we go further or go forward how do you feel, this little daughter will die, maybe the crowd will come together and press her, and she will die.’ I told her, ‘Go back home with my father and after that I will see what will happen.

In the end Ebraheem was evacuated without his wife and children who still remain in Afghanistan.

Participants recounted waiting in the crowds outside the processing centre at the Baron Hotel for several days. The conditions were atrocious and many of our interviewees described being without food and water. Liqman recounted:

the British Army were providing some bottles of water but that was very rare, it was not enough, just they were throwing them to the crowd and everybody who are more stronger or taller they could catch it, all people couldn’t catch it.

Liqman, who waited for two days and two nights outside the Baron Hotel with his young wife, mentioned the total lack of any facilities such as toilets: ‘the most difficult thing was that there was no toilet for two days, especially it was really difficult for women, it was terrible’.

For those participants who waited in the queue with young children, the situation was especially difficult. Baseerah, her husband and four young children soon ran out of the little provisions they had brought with them: ‘just sleeping on the ground with very warm weather and also lots of flies… just lying on the grass for two nights without proper food’.

Moreover, several participants reported hearing gun fire close by and were fearful of being hit in the crossfire. Baseerah explained ‘there was a lot of gunfire’ and the children were terrified because of ‘continuous gunfire and shots.’ Similarly, Liqman reported that people near him in the queue were shot: ‘I have seen two people that have been injured because of bullets’.

As well as the appalling conditions, people were also very worried about getting processed in time before the situation deteriorated even further. Despite having the correct documents, there seemed no guarantees about getting through to the airport. Several participants told us about their desperate efforts to get through the crowds and be processed. For example, Ebraheem described how he waded through a canal of filthy water trying to find British soldiers:

there is a big dirty water and I put myself there and I ask for the army, the British Army. They answer me ‘no’ they are Americans. I go forward and ask from the next soldiers, ‘Are you British?’ They said, ‘No, we are German’. At the end there were British soldiers ... I came to them at 7pm, they said to me, ‘You should wait for tomorrow at 8am’, and one night I was in that water…I showed my email to them, and they took me out from that and said, ‘You go’.

Some participants told us that the British authorities were suspicious of fake emails and thus were reluctant to accept documents at face value. Malala, a young woman, recounted: ‘they couldn’t trust our email document, because they say that, “Everyone has it and it’s fake”’. Malala also told us about her desperate efforts to get through to the British authorities. Having waded through the filthy canal for four hours shouting out for soldiers to accept her documents, Malala finally found two female British soldiers who were willing to listen to her: ‘they helped me, they found me inside the water, where I stood, and then I handed her my email, and then she noticed and checked my sisters’ name, and then we were allowed to get in’.

All our participants were immensely relieved to be evacuated and expressed their gratitude to the British authorities: ‘I’m really thankful of this British Government because they brought us from that bad situation’ (Nasreen). Nonetheless, there was also a view that many vulnerable people had not been evacuated: ‘many other people who deserve to be evacuated, they were left behind’ (Malala).

Overall, there was general agreement that the evacuation process was precarious and having the right connections was often a key factor in negotiating safe exit from the country. As a key informant from a local authority noted: ‘the emphasis on the connection with the British that was used to organise the evacuation doesn’t map onto any of the international instruments that determine who should be getting protection’.

Abubakar explained how his evacuation was made possible by a connection with a British official who helped him to get all the necessary documents. Similarly, when Malala finally managed to get into the airport, she had to draw upon her connections to influential British people, including a well-known journalist: ‘they interviewed me, and they also called [journalist’s name] and the British Embassy in London…they called, and they approved that we were eligible to come’. By contrast, Malala recounted the situation of an Afghan policewoman, who was at risk from the Taliban, but who lacked any influential connections and was denied the opportunity to be evacuated.

Participants described the overwhelming sense of relief when they finally got on the planes to leave Kabul. However, their emotions were very mixed as they considered those left behind: ‘It was kind of joy that I was safe, and it was really sad that I leave my country behind, a lot of friends behind’ (Malala). Moreover, having never been to Britain and not having expected to suddenly relocate to this country, people had absolutely no idea what to expect upon arrival.

However, among our diverse sample of participants, we also heard accounts of those who were unable to be evacuated on time from Kabul airport. Zaman explained that his brother, a senior Afghan army officer, who had the correct documents, tried on several occasions to reach the airport, with his wife and children, but could not get through the crowds before the evacuation process was terminated. That brother is now in hiding in Afghanistan and Zaman is fearful for his safety. Similarly, Mirwais had not managed to get to the airport and was forced to leave Afghanistan via another route:

On the 15th August I was in Afghanistan, when the Taliban took over the control of Kabul, I was in the city … I tried too many times to go inside the airport, unfortunately the Taliban were firing at the people…So I decided to escape from Kabul, and I was crying when I left my country. So when someone is leaving his home, so I was walking along the borders to Pakistan, so I entered Pakistan.

It is apparent that the evacuation was hurriedly arranged and chaotic, with a lack of basic provisions including water and toilets. Our findings confirm other sources by indicating there was insufficient personnel on the ground to process the huge numbers who sought to leave[14]. It is equally apparent that not all those who were most at risk have been successfully evacuated. Our data suggest that knowing ‘the right people’, having good connections, was a factor in ensuring safe transit out of Kabul airport. It is necessary that lessons are learned by government departments and that any future evacuations from any other country does not repeat the same mistakes.

3. Bridging and Contingency Hotels

Many of our participants have lived in ‘bridging hotels’ in/near London for over one year and we are keeping in touch with them via email to monitor any changes. Those who arrived in the evacuation from Kabul Airport in August 2021 had to self-isolate for 2 weeks in ‘quarantine hotels’ before they were moved to bridging hotels. We also interviewed people who arrived via other routes (including unofficial routes) and were accommodated in ‘contingency hotels’, often cheaper and lower quality accommodation than bridging hotels, that also offered far less support.

It has become apparent that the UK government has accommodated Afghans in two very different kinds of hotels depending on their routes of arrival. While people who arrived through cross-Channel migration were accommodated in contingency hotels, those evacuated from Kabul airport in 2021, and who are going through the resettlement process, were accommodated in mainly ‘high end’ hotels, including five stars ones. One of our key informants from a local authority suggested that these processes have created ‘two types of Afghans’ when, in reality, there is no difference between them: ‘while those living in bridging hotels will be allowed to work and claim benefits… the others are stuck in limbo, in a hotel where meals are provided with £8 a week’[15].

On the positive side, most participants in bridging hotels expressed their gratitude to British authorities for providing accommodation to refugees in comfortable hotels in nice and secure areas in London. Abubakar for example, praised the British government for providing Afghan refugees with lots of facilities, in five stars hotels at no cost. To him, ‘we have everything. The food is very best, lunch, the dinner, and the breakfast’.

Several participants praised the role of NGOs in promptly mobilising to assist and advise new arrivals. Baseerah, a mother of four young children, who has limited English language proficiency skills, praised the work of Afghan organisations for providing interpreting skills when reading emails, making GP and school appointments, organising meetings with the Home Office and with the Job Centre, and providing advice on their application to Universal Credit. Hamida, who has two children, praised the work of Hopscotch in organising swimming training programmes, English language courses and a kid’s playgroup for Afghan refugees in the hotels: ‘this organisation is working brilliant’. On visiting the hotels, we observed many such NGOs, including Afghan organisations, running advice sessions in the bridging hotels. By contrast, one participant in a contingency hotel, Sher Shah, told us he had no access to any such forms of information and support.

For those participants in hotels, their main concern was the long waiting times and complete lack of information about their legal status and the resettlement process timescale. Our interviewees were not aware of when and where they would be relocated. Some participants explained how the lack of information exacerbated their anxiety. Participants were concerned that they would be moved around the country from one hotel to another at short notice, and that children’s schooling would be disrupted. This concerns proved to be well founded. Through follow up emails, during the summer of 2022, we found that some of our interviewees had been moved to hotels outside London at short notice. Such was the case for Sher Shah, who was suddenly informed by the Home Office that he would be moved to another hotel outside London. Liloma and Mirwais have also been moved to hotels outside the capital. Moving around the country from one hotel to another, at short notice, disrupted study and work plans.

Although participants were very grateful for the hotel accommodations, some expressed concerns about the lack of space for children to play. As a result, other residents complained that children were running around and making noise. Some complained about the lack of privacy for families at the hotels. Hamida, who is studying to complete her medical studies, noted the lack of facilities in the hotels: ‘I can’t study in the bedroom. My husband is here, the children are coming’.

One key informant from an Afghan organisation said that some people, particularly those who had enjoyed relatively privileged lives in Afghanistan, were embarrassed to ask for information or make use of the facilities provided at the hotels: ‘and as a result, they missed a lot of opportunities and lots of benefits. And now they are in a stage that they have run out of everything’.

Several participants, especially those from ethnic minority backgrounds, described some negative experiences in the hotels. One Hazara woman told us that other Afghans in the hotel had been rude to her and called her ‘Chinese’. She had raised this complaint with the hotel authorities and the local council had sought to address some ethnic tensions between Afghan residents in the hotel.

Despite expressing their gratitude to the British authorities for hosting them in hotels, our participants emphasized three main concerns. First, the long waiting times and total lack of information about their legal status and the timescale for resettlement; this would require more transparent communication from the Home Office to avoid uncertainty and some tensions at the hotels. Second, the need to provide proper spaces and activities for children. Third, to address some instances of ethnic tensions between Afghans in hotels, there is the need to engage those groups in common activities to get to know each other better.

4. Immigration Status

For participants who were awaiting immigration decisions, the main concern was the complete lack of information about their legal status and the long delays in the resettlement process timescale. Our interviewees were not aware of when their status would be confirmed and, as discussed in Section 6 Employment, this had serious consequences for their rights to work, but also heavily impacted on participants’ mental health and wellbeing.

For instance, Liqman reported not receiving information about issues related to financial support, and that there were considerable delays between registration and activation of Universal Credit or receiving the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP) card (respectively five weeks and two months). Liqman highlighted that such lack of information does not allow refugees to make any plan: ‘We don’t know what will happen tomorrow… so I cannot plan for anything’.

As illustrated in previous sections, our data show the diversity of routes that Afghan people have taken to come to the UK. Besides those directly evacuated from Kabul airport in 2021, we also interviewed people who arrived via other routes, including unofficial ones. For example, Sher Shah, a 24-year-old man, unable to be evacuated, paid traffickers to travel from Afghanistan via Turkey and Greece, on to the ‘Jungle’ in Calais and then by sea to Britain. Arriving on British soil he sought out a police station, claimed asylum and was promptly arrested. Because of the current situation in Afghanistan, the UK government has paused deportations, so Sher Shah was eventually moved to a contingency hotel.

As noted by several of our key informants, the government has accommodated recently arrived Afghans in two very different kinds of hotels depending on their routes of arrival. While evacuees from Kabul airport were accommodated in mainly ‘high end’ hotels, Afghans who arrived around the same time through cross-Channel migration, like Sher Shah, were accommodated in cheaper contingency hotels. The difference in treatment is not simply about the type of accommodation. We also noted that while extensive support systems have been put in place for evacuees in bridging hotels, there is little or no support provided in the contingency hotels.

One of our key informants from a local authority emphasised that these processes have created ‘two types of Afghans’ and ‘a completely artificial, false distinction’ based on route of arrival in the UK when, in fact, there is no difference between these people who are fleeing the same situation at the same time.

As mentioned previously, our findings illustrate how people’s experiences and opportunities are shaped by the wider political context and events that operate beyond their control; these circumstances can change suddenly, in unexpected ways, with consequences for immigration routes. Even those who had previously held secure roles with specific immigration statuses, can find themselves plunged into new and unfamiliar situations as they navigate complex, slow, bureaucratic processes.

Four of our participants had arrived in 2020 on student visas to attend British universities on prestigious scholarships. These participants had all competed at the highest level of academic achievement and were planning to return to their jobs in Afghanistan once they had completed their Master’s degrees. With the government’s collapse in 2021, these plans were turned upside down. Unable to return home, these four had to apply to change their status from student visas to asylum seekers. Those who had arrived on student visas were outside of the hotel settings and all faced serious difficulties with accommodation. Dilaram had arrived in the UK in September 2020 and since then she has been living in the university students’ accommodation. However, the university can only provide accommodation to her until the end of her visa or when she graduates: ‘I cannot get an accommodation outside because it is costly, and I don’t have a valid visa. No one can give me a contract for a house’. Dilaram faces an uncertain future as her status is not yet clarified and, having completed her studies she needs to leave the university halls of residence, but she is unable to access private rented accommodation.

Of course, not all our participants neatly fitted into specific migration routes and categories. As the experiences of the students mentioned above illustrates, immigration status can change over time in unexpected ways.

Some of our participants had travelled back and forth to the UK on numerous occasions and via different immigration routes. As mentioned elsewhere in this report, Gulkan originally arrived in London in 2011 for work-related reasons. He later returned to Afghanistan and was again posted back to London with his job in 2017. He expected to return home, but these plans were suddenly disrupted in 2021 with the rapidly changing political events in Afghanistan. Thus, like the students mentioned earlier, Gulkan had to apply to change his status and suddenly found himself claiming asylum in the UK. Having occupied a high level and respected position in Britain, Gulkan now finds himself immersed in the slow and highly bureaucratic Home Office procedures without any power to expedite the process.

Mirwais had also spent time in the UK in the past. Mirwais and his family had visited Europe regularly for business reasons and had travelled to the UK for holiday on tourist visas. ‘So, I used to come to the United Kingdom several times when I was [working] in Paris. My wife and my kids, they came several times here for a visit, families or holiday.’ Yet now, like many others, Mirwais finds himself in very different circumstances and caught up in the uncertainly of the Home Office systems:

my expectation was that I have visa when I arrive to the UK, I can apply for family reunion to bring my kids, they are depending to me. So since six months I’m here, I stop in a hotel in South London, honestly speaking, I am an asylum-seeker now.

Our findings show how diverse groups of Afghans, including evacuees, those arriving via unofficial routes, but also those who were already in the UK on student or work visas, are now immersed in slow and complex bureaucratic processes to secure their status. Waiting many months to receive information from the Home Office is not only causing stress and anxiety but also impacts on their housing, right to work and education. There is a need for more open and transparent communication from the Home Office about the status of immigration applications. Staffing issues at the Home Office need to be addressed to make the process speedier and more efficient.

5. Rehousing

Apart from securing their immigration status, another big concern for people in hotels was rehousing. Participants, who have lived in bridging hotels for almost a year, complained about the lack of transparency and information from the Home Office about when and where they might be re-housed. Liloma told us: ‘When we asked them how long we should wait for a house and other information they always tell us, “We don’t know. Just wait and we’ll let you know … but still none of us know about the future’. Another participant, Hamida, said that the Home Office had stated simply there were not enough properties in London for all families.

A key informant from a local authority, explained that the Home Office asked all the London boroughs to get involved in the resettlement process of Afghan families:

Someone else in our team would say to the Home Office, “We have this property,” and the Home Office would come back and say, “We have this family.” And that’s the point that we get involved.

However, she explained that in reality the inefficient administration of cases was slowing down the process. That local authority had identified several properties in their borough but, so far, the Home Office had not found families to take up all these properties. A key informant from another local authority stated: ‘our Council has taken on an additional housing officer to try and speed up communication and processes of getting people settled’. Another key informant from a different local authority described similar delays in receiving families; even though they had identified some available properties in the borough, the Home Office had not allocated families to take up these vacancies, which resulted in the council losing money on those properties.

Many of our key informants and interviewees pointed to under-staffing at the Home Office as hampering the re-housing process. While some Home Office personnel were described as helpful, it was apparent that they were overburdened and struggling to cope with the pressures of the system. One key informant described the Home Office pace as ‘glacial’ and complained about complex bureaucratic processes and lack of clear channels of communication. Several key informants stated that the Home Office did not communicate regularly and sufficiently with the local authorities, an issue which further exacerbated the rehousing process.

For hotel residents, especially those with children, waiting in hotels for months on end was becoming exasperating. Baseerah expressed her fear that the Home Office would keep families in hotels ‘for one more year’. During a dissemination event in July 2022, we met up with Malala, who informed us that she and her sisters were still in their hotel, almost a year after their evacuation. In follow up emails in August 2022, Malala informed us that the HO had instructed her to find her own privately rented accommodation[16]. It seems that after one year, the HO is now attempting to move people out of hotels and into the private sector.

The lack of information and the possibility to be relocated anytime and anywhere in the UK was upsetting many participants. For example, Liqman, who was living in a hotel room with his pregnant wife, heard from the Home Office that they may be relocated to other hotels in Aberdeen, Leeds or Manchester because London hotels were very expensive. Indeed, his fears proved to be well founded because, when we followed up with Liqman by email in August 2022, he and his family had been moved to a hotel outside London.

Many participants wanted to stay in London and close to their current hotels, if possible, because of wider networks of relatives or friends or a general sense of Afghan communities in the city. For example, Nasreen notified the Home Office that she preferred to stay in London because she wants to live near her 90 years old grandmother, who is a long-term resident of the city. Although they had wished to stay in the London area, in follow up emails, we found that one participant, Hamida, and her family, finally had been rehoused in a flat in Yorkshire. Even those who expressed their willingness to move outside the city, seemed to be still waiting months and months for relocation. Such is the case with Baseerah, who expressed her preference to the Home Office to relocate in Manchester, where she and her husband have extended family and friends.

Spending almost one year in a hotel in central London had also given some participants expectations about what life in Britain was really like. For example, Malala told us that families who had a ‘very fancy home in Afghanistan were expecting the same kind here’. In our interviews, we also noticed that most of the hotel residents had not travelled outside of central London and so had no sense of how most ordinary residents actually lived. We heard some anecdotal evidence from interviewees that a few families were unhappy with the accommodation offered, because it was in outer London boroughs, in unfamiliar areas, not close to their hotels, or did not conform to their expectations, and so had declined the housing offer. We also heard from some key informants in local authorities that some families were expressing a preference for particular kinds of accommodation based on what they were used to in Afghanistan. We cannot verify the frequency of this occurrence, but this may partly explain some of the delays in matching families and properties.

One of our key informants from a local authority highlighted that the lack information shared with the families may create a high level of expectation leading to disappointment. By the time local caseworkers meet with them, the Afghan families are often surprised and unprepared:

It’s not what they’ve been told. It’s not what they’ve been advised… They’re not prepared for the abundance of paperwork… even when we’re trying to be slow and clear with interpretation.

In this respect Ebraheem, who was trying to bring his wife and children from Afghanistan, expressed his confusion about the whole relocation process. He explained that the Home Office told him that he was moving to a house by himself, but he moved to a shared flat with two other men. The lack of privacy exacerbated his diagnosed anxiety: ‘I faced some difficulties that I cannot share with my family because they are not here’. Later, he emailed us to say that he moved from that accommodation to a rented house with Afghans friends. He moved in search of a cheaper accommodation in a town in the Midlands where he could find a job and send money to his family in Afghanistan. Hence, we believe it is very important to follow up our participants as they move out of the hotels to see how they are coping with life in ordinary society.

Indeed, interviewing people in hotels, we often observed that they were not well prepared for the reality of living in a city as expensive as London. For example, when interviewing Baseerah in her hotel room, she was very positive about how easy life seemed in London and in the UK generally. Currently, Baseerah and her husband are learning English. As mentioned previously, they have four young children. Baseerah’s husband is looking for a job but feels that he will not be successful until his English improves, and they are currently receiving Universal Credit. It is hard to imagine how they would manage financially to support themselves if moved to a flat in London, especially in the current context of the spiralling cost of living.

Our findings highlight the lack of transparency and information from the Home Office about when Afghans might move out from hotels and the anxiety this situation is causing. This has been a hugely expensive programme with little to show at the end of one year. By August 2022, almost 10,000 Afghans were still in hotels awaiting re-housing[17]. There is a need for more transparent and regular communication from the Home Office to avoid uncertainty, tension, and false expectations among people, as well as improved communication between the Home Office and Local Authorities to identify suitable properties and speed up the process of allocation. It is also important to inform people about the various areas and types of houses available to them, especially outside central London, as well as the reality of living in the capital; this would ensure that current hotel residents are better prepared for the reality of high living costs, especially in the context of current cost of living crisis, soaring energy prices and rising inflation rates.

6. Employment

The employment picture among our participants was quite varied. Some of the long-term residents in London had rebuilt successful careers and were thriving. A key informant told us that Afghans were hard working, and many had established flourishing businesses in London. Moreover, we were told about many of the second generation, the children of Afghan migrants, who had graduated from university and obtained professional jobs in areas like accountancy and law. However, our rich data show a range of diverse experiences.

Among the recent arrivals, especially those who were still in hotels, there appeared to be confusion about their rights to work. Ebraheem, as noted in the previous section, was one of the few participants who had been rehoused from a hotel. However, he described his ongoing difficulties in getting a job: ‘I wash two days non-stop dishes in a restaurant, they said, ‘’You have insurance number, you have a bank account, but we cannot pay. Why? Because you don’t have proper documents”’. There was a general sense of frustration about the slow process in securing the right to work, as Ebraheem explained:

I have done a biometric and still waiting for documents. So I don’t receive any other call from the Home Office about the documents or requirements, I’m just waiting for them. But I have biometric, and they filled the form for me for permanent residency.

Similarly, Nasreen had several interviews for café and hotel jobs but the lack of clarity about her right to work was a recurring problem:

The Home Office said “you’re allowed”. Also we have got a letter that state that “you are allowed to work, to study” … But when we are going for a job, in the middle of the interview they want like ID number or something, reference number or something but we do not have that. They are saying that without that “we cannot give you a job, we cannot hire you”.

Although Nasreen has a national insurance number, she had not yet received her Biometrics Residence Permit (BRP). Many participants were frustrated by how slow the Home Office was in processing employment rights. Although many people had their biometrics interviews, there seemed to be a long delay before their status was confirmed and hence there was confusion about their right to work.

Nonetheless, even though participants’ right to work was unclear, many told us that Job Centres were putting them under pressure to look for work. Ebraheem said:

every time the Job Centre are giving us lot of appointments and they are telling us that, “Why you don’t find the jobs?” We are answering that we are looking for a job.

Baseerah and Liqman also complained about Job Centres: Baseerah stated that the Job Centre was not actually helping her husband to find work, while Liqman complained about being constantly invited to various appointments, sometimes several times per week. His wife, who was heavily pregnant, was also continually being called by the Job Centre, although she was unable to work at that time.

Most of our participants were highly qualified and had professional jobs in Afghanistan. They were keen to work and reactivate their careers in Britain but were very worried about de-skilling. Abubakar, who held a senior government post in Afghanistan, recounted some advice he received from friends in London:

they told me “Don’t work in the Pizza Hut” and minicab in the Uber, “you should work with the government or in the charity”, like this kind of project.

However, despite being multi-lingual, he was worried that his lack of English proficiency would limit his career options in Britain: ‘I can improve my English because my English is a little bit weak. I will improve my English, but I can speak Pashto, Urdu, Dari, a little Arabic’.

Zaman was a qualified doctor with many years of experience in Afghanistan. He had arrived in Britain in 2020 to pursue a master’s degree. Having arrived on a student visa, he was now applying for asylum. He was deeply concerned that his career was now over, and he would never be able to work as a doctor: ‘You know medicine is seven years in Afghanistan… I got specialisation, which is three years, that’s 10 years. I got a degree and PhD two years, so it was 12 years… But here, I’m nothing… I think I am lost here, yes’.

Another qualified doctor, Rabiya, had been in London since the early 2000s, but during that time she had not managed to restart her medical career:

I’m looking now for job for healthcare assistant or for phlebotomy, to take blood samples… quite an easy job… No, I couldn’t find jobs. I study a lot but I couldn’t pass my English STAT exam. This was my problem, I finish ESOL level two and then functional English, then I did try to get pass STAT exam, I couldn’t pass the exam.

Rabiya emphasised English language fluency as the key stumbling block in restarting her career and differentiated between everyday English and professional English: ‘If you want to learn simple English to talk with people everyday life, it’s easy, yeah, but, academic language, I have to know academic language. It’s very hard’.

Among our participants we also interviewed several Afghan young people in their 20s, who were studying at London universities. Despite gaining qualifications from British institutions, they expressed some concerns about their employment prospects. One issue raised was a lack of professional networks. Shabnam, a recent law graduate, observed: ‘I have also seen people, I have applied with people for some positions where they had connections and I didn’t have, so they get the job.’

Another issue raised by these young graduates was negative stereotypes of Afghans, especially Afghan women. Dilaram explained:

Like if you were Afghan you were definitely involved with terrorist activity… so obviously like if you’re an Afghan definitely… a little bit of a label, so your CV is at the bottom because it disadvantages you because of the background that you have, the background that you came from. And another thing, so if you’re an Afghan woman for example, there’s always have been like things about Afghan women, ok, we may face some problems because in terms of courage, in terms of commitment, in terms of freedom of movement.

In other words, Dilaram perceived a prejudice among some employers that Afghan women would not make good workers because of so-called ‘traditional’ values, especially concerning their freedom of movement to travel around for work meetings.

Overall, among many of our recently arrived participants, including those in hotels and those who had arrived via student routes, there was a sense of having to start their careers from scratch. Baryal, who graduated from a British university and also had experience working for international organisations in Afghanistan, stated: ‘when you come to the UK you have to start from scratch, like working from very starting positions’. This point was echoed by Hamida, an evacuee: ‘we are starting from zero here’.

Therefore, we can highlight three key issues. First, the need to clarify and expedite the right to work for recently arrived Afghans; this would also require better coordination between the Home Office and Job Centres to avoid persistent confusion. Second, there is a need to provide mentoring, advice and networking opportunities for people to enhance their chances of securing professional jobs commensurate with their qualifications. Third, English language proficiency is clearly a priority. It is apparent that people are held back from realising their true potential, including longer term residents, especially women, and thus better support around language development is needed.

7. Education

More than half of our thirty participants, both from the older generation and new arrivals, were highly educated. Many participants had studied at university level, either in Afghanistan or in other countries, such as Russia, Poland, and Iraq while for others education opportunities had provided them with the possibility to come to the UK (see section 1. Diverse routes of arrivals and immigration barriers). Despite the generally highly educated profile of our participants it was noted that many who had been living in the UK for longer, including several women, had experienced de-skilling and were unable to practice their profession (see section 6. Employment).

Participants who had not had the chance to gain an education in Afghanistan or in other countries, emphasised their children’s educational success in the UK and were most proud of their achievements[18]. For many people, education was seen as a way towards social mobility and economic stability, and educational achievement was perceived as a marker of success in their own migration experience. Witnessing their children thriving in their new environment made the (often) difficult migration journeys and the sacrifices associated with them worthwhile, a theme that is reflected in wider migration literature, and that was also highlighted by Ahmad Shah:

their children do very well. Because of the fact that the vast majority of Afghans have been deprived themselves from proper education back home … when they come here they can see the value of education for their children ... So, second generation Afghans are successful, I would say, and they’re doing very well at schools, very talented. And one of reasons probably is the fact that their parents are pushing. Because they have been deprived themselves, they want to make up for that by bringing up their children properly, sending them to good schools and all that.

In some cases, migration, education, and safety were closely linked. Ghorzang for example, sent his children to the UK first, not only to remove them from risks in Afghanistan, but also to provide them with opportunities which would allow them to improve their situation and in turn help their family:

And before … I came to this country I sent my children, they got their education. This country gave them education. They have now very good jobs. Their income is quite good, and by the help of them, then following we could come, we could manage to come to this country as well.

For newcomers, access to education and particularly to English provision was crucial to restart their career or gaining new additional qualifications. Zaman’s wife for example was keen to get involved in business, however she first needed her English qualifications. As she was dependent on her husband’s status, she was not yet eligible for English classes, a fact that seemed to cause some frustration for both, as explained by Zaman:

…always she is asking me when she can go to English classes but still she is not eligible going to the school, to classes, English classes … She, I already told you, that she depends on me, her status is dependent on me. Yeah, it is [stressful].

Many of the new arrivals were enrolled on ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) classes, and could also access college, although the process was not always clearly explained and left people confused as to which provision they could access. This was the case for Liloma, who had wanted to start college as soon as possible but was told she had to wait. By the time she received the go ahead, Liloma had missed the deadline and had to wait until the following semester. It was also noted that there was great variety in the educational needs of new arrivals. Although English language was a clear priority for many people, some recently arrived people spoke fluent English. These participants, usually younger generations, had learned English in Afghanistan, for example at the American University, and were looking for different development opportunities which were not being considered by the government and the support services, as Shabnam commented:

Like all of us don’t need a course for English right now … it would be nice to have a survey maybe and see where everyone are right now and then try to come up with [something] based on their needs.

Another concern for new arrivals was settling children into schools. For participants who were living in hotels, this process had been managed and organised for them by local authorities. Our key informants and parent interviewees agreed that the process of assigning children to schools had gone smoothly. Nonetheless, this process was not entirely without challenges. Baseerah, a mother of four, explained that her two school-age children had been assigned to a school that was far away from the hotel and required them to take the bus, while her other two children were assigned to a nearby nursery that could be reached on foot. This meant that she and her husband had to share school runs in different locations, as well as fit them around their own ESOL course schedules.

Henceforth, the availability of school places is likely to become an issue. Two of our stakeholders explained how initially it had been easy to find availability in schools because the numbers of people being rehoused in specific boroughs were still very low. Nonetheless, it was noted that if the numbers of people being moved to certain areas increased quickly, schools might need to apply waiting lists. Furthermore, as people are starting to be moved out of hotels and rehoused in other areas, or outside of London, children will need to be transferred to different schools.

On a positive note, children were generally recognised to be easily adaptable, and most parents reported that their children were happy and had settled well into school. The process of settling in was easier for those who already spoke some English or who had studied the language in Afghanistan, as Zaman commented:

[My children] they are very good, even more than my expectation. When I was in Afghanistan they were going in a good quality school, their lessons were in English and they used to study in English and this is why it was a bit easy for them to integrate.

In contrast, for children who did not speak English, like Yosra’s children, schools adopted creative solutions to help them participate in school life:

Especially for my children it was very hard … because they didn’t know English. That was very hard as well for, I remember for my son, [he] talk[ed] after four months in school … [In] school… they have some placard around the neck and they show the teacher this placard. For example, one of them for water, one of them for play, one of them for, for example I’m hungry, and something like this. Everything they want, the[re is a] placard [for].

English could be a barrier also for some parents. Baseerah explained that the school had an Afghan interpreter, who was present whenever there was an important meeting or issues of public interest were being discussed; however, for basic daily communication, parents and teachers relied on Google Translate. In some cases, there had been episodes of miscommunication, but this was generally on matters of lower urgency.

Language courses and education provision were important also for those participants who had come to the UK to join their husband or to get married. Often these young women did not speak any English or had basic knowledge of the language. Most of these participants had enrolled in beginner courses, but had to stop once they had become mothers, as explained by Maryam:

I start to study my English [on a course], from alphabet, from beginner, and for one year only, and then I got my children.

When we interviewed her, Maryam had re-started college and was going to classes at night-time, however she still found it stressful to balance her education with her home life. Limited time and lack of child-minding provision were recognised by most women as the major barrier to education, as expressed by Khdija:

At least I have to learn something, at least I have to learn English. There are not some place you can go with the children and we can study. … I want to study.

Structural barriers, like visa restrictions, further complicated access to education opportunities for this group of women; this was the case for Changa, who was told by her college that due to the limited remaining time on her visa they couldn’t enrol her. Despite the difficulties with access to education and balancing study- and home-life, these women held high aspirations for education and eventually for employment.