Mercedes Vicente

It matters what ideas we use to think other ideas with.

—Marilyn Strathern

What does it mean for a river to have standing? In 2017 the Whanganui River in Aotearoa New Zealand became the first river in the world to be granted personhood rights in recognition of the local Māori tribe's kinship to the river, which they see as their ancestor. What happens when a river is conceived as a living entity instead of the prevailing perspective of human sovereignty over nature? What political impact may this unprecedented legal status have on the ecological crisis? What do Indigenous cosmologies contribute to current posthuman philosophical debates?

We will explore how a frame — a departing question, thought, assumption, perspective, field of knowledge, methodology, or narrative sets up a path that leads us to a destination exponentially different in constructing ideas. It does indeed matter what ideas we use to think of other ideas with. 'Matters' also implies an ethical stand, that thinking comes with response-ability, recognising the ethical implications of our chosen frameworks, and an awareness that may prompt us to act and interact differently. Donna Haraway's notion of kinning is based on responsibility and becoming-with: a way of making persons (not just humans) beyond the Anthropos and sustainable forms of living with each other, of "getting on together", in a practice of relationality.

Through ecocriticism, we will engage in theoretical approaches and the reading of ecoliterary texts that challenge our inherited duality of the human and non-human world. We will explore ethico-politically responsive environmentally frameworks to the provocation of "a river with a standing".

Studio bibliography

- Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2010.

- Bradiotti, Rosi and Hlavajova, Maria. Posthuman Glossary. London and New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

- Christopher (ed.) Animism in Art and Performance. London and New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan, 2017.

- Demos, T. J. Decolonising Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016.

- Guattari, Felix. (1989) The Three Ecologies. London and Brunswick, NJ: The Athlone Press, 2000.

- Haraway, Donna J.. Staying with the Trouble : Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016

- Klein, Naomi. This Changes Everything. London: Penguin Random House, 2014.

- Latour, Bruno. “Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene”. New Literary History. Vol. 45. No. 1.

- Aldo Leopold, Think Like a Mountain. London: Penguin, 2021.

- Serres, Michel. The Natural Contract. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

- Stone, Christopher D. ‘Should trees have standing? Towards legal rights for natural objects’, Southern California Law Review, 45 (1972), pp. 450-501

- Tsing, A. The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021)

Eco criticism / Eco writing / Eco fiction

- Bradiotti, R. and Hlavajova, M. Posthuman Glossary (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018). See entries (Material) Ecocriticism (pp. 112-15) and Storied Matter (pp. 411-14)

- Clark, T. The Cambridge Introduction to Literature and the Environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Clark, T. Ecocriticism on the Edge. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

- Oxford Definition of Ecocriticism and bibliography

*

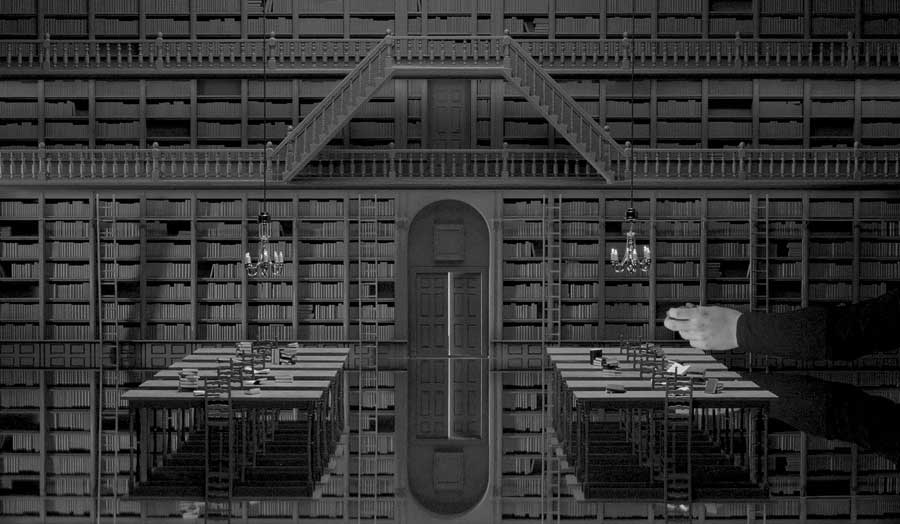

Studio image: Nova Paul, Ko ahau te wai, ko te wai ko ahau (I am the water, the water is me), 2018. Banner: Hans Op de Beeck, Staging Silence (3), video still (detail), 2019

Details

| Tutor | Mercedes Vicente |

|---|