Date: 18.10.2011

Ten years after the United States and its allies launched their invasion of Afghanistan, I have been reflecting on a major moment in another of the conflicts which followed the attacks of September 11th, 2001. I am posting an extract from my article, ‘Capturing Saddam Hussein: How the full story got away, and what conflict journalism can learn from it’, which is published in the current issue of the Journal of War and Culture Studies. The article is based on my experience as a BBC correspondent in Baghdad at the time of the former Iraqi leader’s capture.

This is copyright material (c) 2011 Intellect Ltd.

EVEN IN THE MIDST of the most technologically advanced war that had ever been fought, there was still a craving for the kind of news that spreads through chance conversations. ‘Is it true?’ asked the soldiers searching the journalists. The reporters were on their way into an unscheduled news conference called by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) on a Sunday afternoon in Baghdad in December 2003. The soldiers’ initial question prefaced their more pressing one, which soon followed: ‘Does this mean I’ll be able to go home early?’

As BBC correspondent in Baghdad that day, I was one of the reporters to whom that question was put. In response, journalists shrugged, or mumbled replies like ‘Well, that’s what we’re going to find out.’ There was impatience in some of their voices. They were in a hurry. They sensed that they might be about to get one of the biggest stories of their careers.

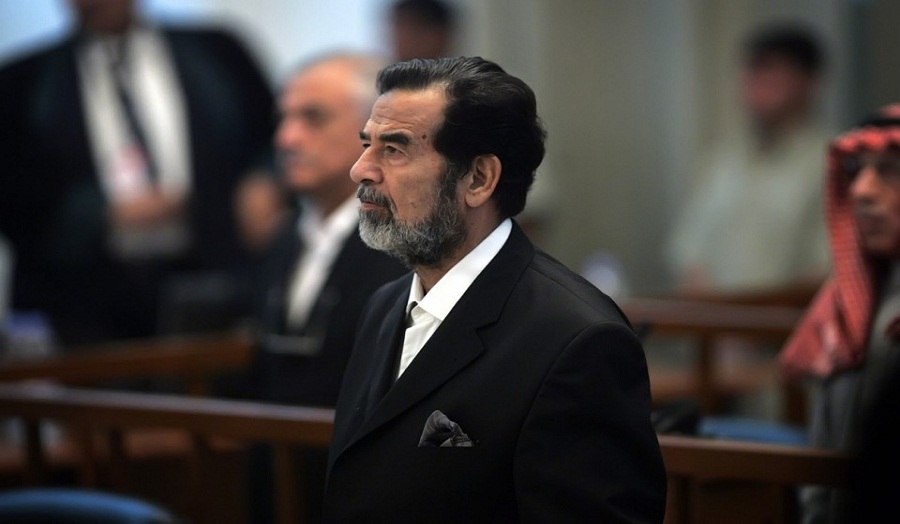

Since early that morning, rumours had been spreading in the Iraqi capital. Saddam Hussein had been captured. The Iraqi leader had been in hiding since the invasion, which had driven him from power. Journalists who called their news desks in foreign capitals, to share the rumours, found that the rumours were already circulating there, too. It became impossible to establish where they had begun.

A sense of chaotic excitement acted as cover for a carefully planned operation that was underway inside the CPA building. At the same time as those wild, breathless, speculative, telephone calls had been taking place between journalists, another, more thoughtful, communication had been in progress.

The occupying powers in Baghdad were preparing to announce that the rumours were true: they had captured Saddam Hussein. Shortly after 3 p.m. that Sunday afternoon, 14 December 2003, Paul Bremer, the leader of the CPA, told the news conference, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we got him!’

Some of the Iraqi journalists leapt to their feet. They cheered wildly and shook their fists in the air. Some of the foreign press did so, too. Others were less sure how to react. Their faces betrayed signs of internal calculation. They seemed to reflect on how they, as reporters taking pride in their impartiality, should behave. They took in the huge professional challenge that lay ahead: time, as always, short – and an afternoon that might be one of the defining moments not just of their career, but of the United States’ career as a superpower. As if to mark that, Washington had planned a major event. Those journalists who did not cheer – I was one of them – were left feeling like churlish party guests who refuse to join in the fun. ‘It seemed as if journalistic rules cherished during “normal” times had to be suspended for journalism to do its job,’ Silvio Waisbord said of journalism in the United States after September 11. That suspension was in force in Baghdad as it had been in Manhattan.

Extracted from: Rodgers, J. (2011), ‘Capturing Saddam Hussein: How the full story got away,

and what conflict journalism can learn from it’, Journal of War and Culture

Studies, 4: 2, pp. 179–191, doi: 10.1386/jwcs.4.2.179_1.

(c) 2011 Intellect Ltd