17 June 2025

When writer and journalist Alex Renton was fossicking about in his grandparents’ house in Ayrshire, he came upon a trove of documents that showed that the family’s wealth could be traced back to the plantations they’d owned in Trinidad and Tobago, and the compensation that they received when their slaves were freed.

Renton had believed his ancestors to be liberals – they read Thomas Paine! – and was shocked by his discovery, although his mother initially defended the family on the grounds that ‘we never made any money – and everyone else was doing it too’.

Renton spoke vividly about his search to uncover his family’s role in transatlantic slavery, the subject of his book, Blood Legacy (whose publication some members of his family tried to prevent), at an event co-organised by the Centre for Life Writing and Oral History (CLiOH) and the Global Diversities and Inequalities Research Centre.

The event marked the five-year birthday of CLiOH, which launched in 2020 with a panel on Writing Black Lives.

The new event, opened by Professor Julie Hall, Vice-Chancellor of London Metropolitan University, showed clearly the hostility that researchers face when they challenge the narrative that Britain ended slavery, and when they draw attention instead to how much wealth it accumulated through sustaining it. Professor Corinne Fowler, author of Green Unpleasant Land, was responsible for the National Trust report on the colonial connections of 93 of its properties. She spoke about the often quite personal backlash against her report, some of it from bad faith actors, even though much of what she discovered wasn’t new – it just hadn’t been put together or curators had averted their gaze. The legacy of colonialism was racism, she observed, which reaction to the National Trust report further excited.

Writing (Slavery-linked) White Lives originated in the research into his own ancestors’ role in slavery in the Caribbean by London Met’s Professor Peter Lewis. Prof. Lewis was helped by the research carried out by Exeter College, Oxford (which generously covered some of the costs of the evening), where he had been an undergraduate. Indeed it was Dr Isabel Robinson, principal researcher on the Exeter College Legacies of Slavery Project (directed by Dr Dexnell Peters of the University of the West Indies) and a speaker on the panel, who uncovered the role played by Prof. Lewis’s ancestor, one of 45 ‘Persons of Interest’.

Dr Robinson showed how the profits from and patterns of entitlement in the colonial world between the 17th and 19th centuries were reproduced in Exeter College and embedded in British society beyond. She contrasted this tellingly with the research that she carried out for Liverpool John Moores University, which, when founded as a college in 1825, was complicit with enslavement both by helping to produce a workforce that could service it and by propagating racial science.

What is the personal cost of doing research like this? The chair, Dr James Dawkins, whose doctorate investigated the history of his Caribbean ancestors enslaved by those of the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, drew attention to the vulnerability of the lone researcher and the toll exacted by their digging.

Various ways of mitigating these personal risks were discussed by the audience, which also warned against ‘slavery porn’ and the risk of white people profiting as authors of such research.

Should white Britons be prepared to admit their culpability, as evidence emerges of the 1.2 million people in the UK today who are heirs to those who received ‘compensation’ for their slaves, Or does everyone gain if the racism of colonialism and its continuing impact are named and faced?

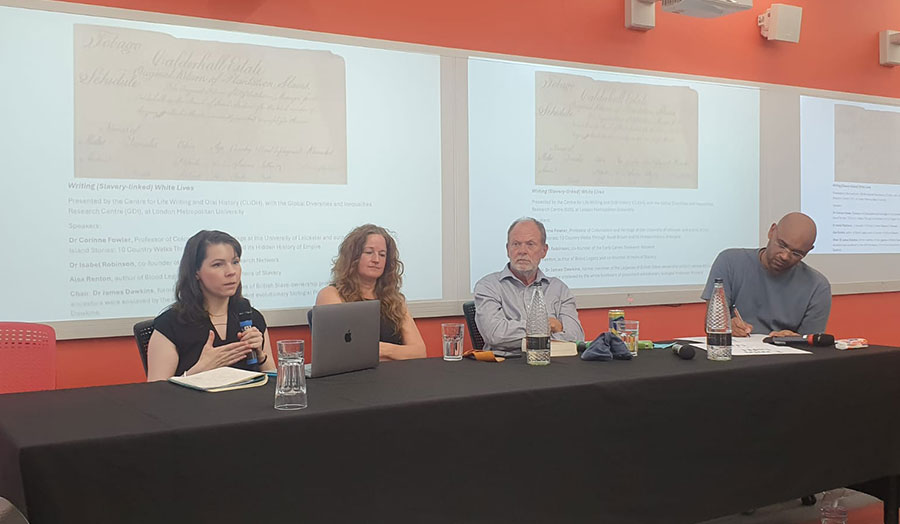

Image: panellists Dr Isabel Robinson, Prof. Corinne Fowler, Alex Renton and Dr James Dawkins